Let’s Talk About Film Cameras

Making a photograph used to be a pretty straight forward and comparatively simple process: you chose a roll of film (either black and white or color with an ASA/ISO* film speed that suited your needs); you chose a lens that had a maximum and minimum aperture; you chose a camera with set shutter speeds, and a light meter. Most cameras had various features that did not necessarily affect the image quality but may have made shooting easier, such as an auto exposure mode similar to DSLRs today, usually aperture preferred.

*ASA: American Standards Association

ISO: International Standards OrganizationPhotographic film and everything connected to it was once a US-dominated product, but by the 1970s other companies in other countries had become major players in the marketplace. The association simply changed its name from ASA to ISO to reflect the inclusion of international partners.

Once you had a lens mounted and film loaded and set the ASA speed on the camera to match the speed of the film, you were ready to shoot. That’s when it got really complicated—you actually had to focus the lens, adjust the aperture and/or the shutter speed (only one if you had a camera with auto exposure like the Nikon FE2 above) and then when the built-in light meter (if the camera had one) said you had a proper exposure, you could click the shutter button—all the while whilst trying to compose your photo.

How did we ever cope? Especially when shooting moving subjects, like flying birds, with a long lens and no image stabilization. Of course we used a tripod, quite often, but that didn’t guarantee sharp, in-focus photos of identified flying objects.

And Talking About Film…

I know film is making a big resurgence amongst a small but growing number of photographers. I can only guess that these photographers are not veteran photographers who “grew up” shooting film, but most likely new to photography and find it quite novel. I think it’s a good thing for photographers to learn about film and film cameras for those are the basics of photography. It’s like learning to sail on a small sailboat.

In some ways it’s similar to the previous resurgence of vinyl records. Is it a fad? An interest for the more affluent amongst us? Vinyl records cost 10-20 times what they sold for new back in the 1970s. Me, I have no desire to return to the days of film, and likewise the days of vinyl record albums, or VHS tapes.

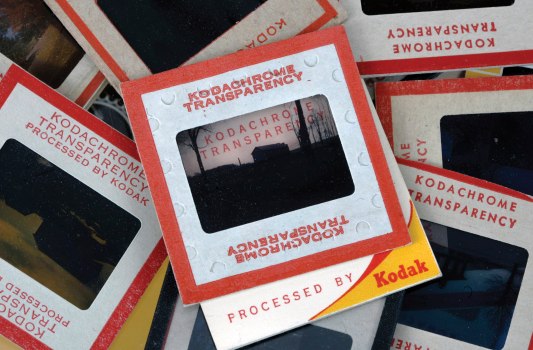

First and foremost film was and still is expensive (at least I assume it is today—I haven’t purchased any film and that’s why my view of it is in the past tense): back in the 70s and 80s a 36 exp. roll of Kodachrome or Ektachrome cost about $5.00. Processing cost another $5.00. You could save a little if you bought Ektachrome or B&W film in bulk and loaded your own film cassettes and then processed that film yourself. You couldn’t do that with Kodachrome, you had to buy it in individual 24 or 36 exposure rolls and have it processed by Kodak. Essentially we paid about $10 per 36 exposures, $100 for 360 exposures—a number I can shoot in just a matter of hours, if not minutes, today.

Film was cumbersome: you had to load it and rewind it and unload it every 36 exposures, and can the exposed film, and that took a minute or so. You had to keep track of those exposed rolls, keeping them safe and dry in their containers and it really helped to label the rolls after exposure. After exposing the film, assuming you weren’t processing it yourself, you had to take it to a lab or mail it to a lab, and then wait for the film to be processed. You could have the negative film printed, as most people did, especially with color film, or have a contact sheet made, as most photographers preferred. With transparency film, of course, you had to view those slides either on a light table (good ones were not cheap)— as all pros did, or in a slide projector, which was risky as the heat could damage the film and was not a good practice.

So shooting was a bit of a laborious process that required a certain modicum of patience. Which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing—we were more careful in our compositions and didn’t shoot aimlessly. Even with a motor drive we were careful, except perhaps when shooting events and weddings. Yes, you could rush processing a bit, and one hour processing became available in many places for negative film. With Kodachrome you had to wait and it could take a couple days or more. Kodachrome was required if you were shooting for major publications like Nat Geo, but then you would just send the rolls to them for processing, not knowing how the photos came out, or again you had to process the film and wait. Before exposure, and especially afterwards, film had to be kept cool. Heat was a destroyer. One further note: Kodachrome came in a red and yellow package and Ektachrome in a blue and yellow package—Kodachrome was more sensitive to reds and Ektachrome more sensitive to blues and greens. Ektachrome also came in a tungsten version for shooting with tungsten studio lights.

Film had some other issues, one such was reciprocity failure: failure of an emulsion to follow the principle that the degree of darkening is constant for a given product of light intensity and exposure time, typically at very low or very high light intensities. For instance, at half of the light required for a normal exposure, the duration must be more than doubled for the same result.

Not a big deal if you didn’t make a lot of long exposures, but if you did make those long exposures and forgot to compensate for reciprocity failure you would wind up with film that was probably unusable.

And of course the biggest limitation of film was the ASA/ISO speeds. Ilford came out with an ASA/ISO 1000 transparency film that worked fairly well for some subjects if graininess could be used to enhance the composition, but it was useless for most purposes because of the graininess. The best film was the lower speeds, like Kodachrome 25 and 64 or Ektachrome 100. Black and white shooters preferred Kodak Tri-X 400, but I always found it too grainy for my subjects.

Kodak made another black and white film that was absolutely fantastic: Kodak Technical Pan. You could shoot it at different speeds from a very low of ASA/ISO 25 up to 400. Depending on the speed you used you would alter your processing which you had to do yourself as none of the labs I knew of offered that service. At ISO 25 there was essentially no grain and the contrast and dynamic range was simply amazing. It was the closest thing to digital that you could get with that variable sensitivity range, but only in black and white. Processing was messy and certainly an ecological hazard; the chemicals were toxic and not good to be exposed to on a regular basis, and they were difficult to dispose of properly.

Do I miss the simplicity of film cameras? Yes, more than a little. But I don’t miss film. The problem with film these days, in my opinion, is the simple fact that you have to digitize it for almost anything you want to do with your final images, and that opens up a whole other little can of worms: you need a really good scanner or a scanning/imaging service to do it for you. Still, there is much to be said for film, especially if you go to medium and large format cameras—resolution and dynamic range can actually exceed that of the best DSLR. For some really good information about film versus digital see PetaPixel’s excellent article Comparing The Image Quality of Film and Digital.

In succeeding posts I’ll be talking more about cameras and about a lot of things photographic, including composition, tips and tricks, and software, but especially gear. If you have something to talk about, talk about it here.

And please come back.